The Carbon Arc Furnace and the Spark of Creativity

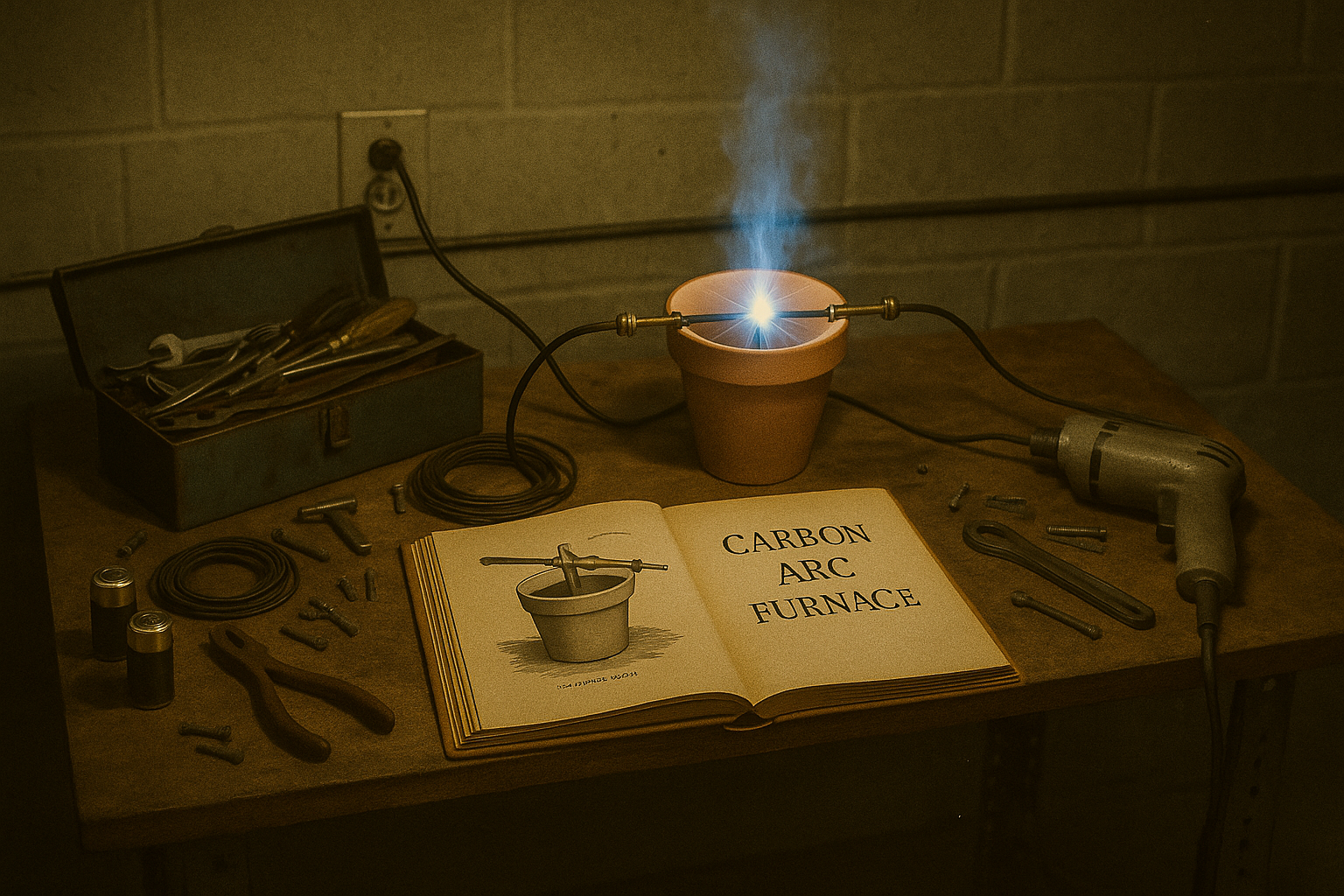

I grew up in Chicago, where winters were cold, dark, and long—and we had to get creative to entertain ourselves after school. In 1974, when I was in 7th grade, my good friend and I—partners in curiosity—discovered a library book titled 50 Experiments to Do at Home with Found Materials. It was the perfect source for our next project. Naturally, we chose the most dangerous-sounding one: “The Carbon Arc Furnace.”

Surprisingly, we were able to scrounge up all the required parts from my parent’s basement: a clay flower pot, D batteries, curtain rod, and an extension cord. We carefully followed the directions, set everything up on the concrete floor, and plugged it in.

The result was spectacular—an intense blue flicker of light and heat that left us both awestruck. The next day, proud of our success, we decided to show our creation to our science teacher, Mr. Tobin. We brought it to school in a paper bag and handed it to him before class. He peeked inside, eyes widening with disbelief. Without a word, he rolled up the bag and placed it high on a shelf in a locked storage closet. When he returned, he didn’t mention the contents—he simply encouraged us to explore “a safer path,” perhaps in life science.

As dutiful students, we took his advice. I pursued a pre-med path in college; my friend studied environmental science. But early on in that pre-med journey, I began to lose my spark. During my sophomore year, my organic chemistry professor opened the course with this advice: “Don’t try to learn this material—just memorize it and stop by my office if you need a recommendation for med school.”

That was the moment I knew I needed something different. The following quarter, I took an introductory design course as an elective—and it reignited everything I loved about exploration, creativity, and problem-solving. I switched majors to product design and engineering, landed my first job at David Kelley Design (the precursor to IDEO), and have spent my career immersed in design and innovation ever since.

What If Mr. Tobin Had Celebrated Curiosity?

I often wonder what might have happened if Mr. Tobin had responded differently. To be fair, our invention was dangerous, and we were lucky not to harm ourselves—or the basement. But what if he had used our curiosity as a teaching moment? What if he had helped us understand the risks, refine the design, and keep experimenting safely?

That simple spark of curiosity could have been transformed into a deeper understanding of science, design, and problem-solving. Instead, like so many young learners, we were steered toward safety and compliance over exploration and imagination.

The Decline of Creativity

Sir Ken Robinson captured this tension brilliantly in his TED Talk, “Do Schools Kill Creativity?” He argued that our education system—designed during the Industrial Revolution to produce factory workers—emphasizes conformity, compliance, and finding the “right” answer over curiosity and creative thinking.

To illustrate the decline in creativity as we age, I often share a story called “The Ever-Shifting Dot” when I facilitate innovation workshops.

In a brightly colored kindergarten classroom, a teacher draws a simple white dot on the chalkboard and asks, “What do you see?”

The room erupts: “It’s a bubble!” “A tiny spaceship!” “A magic seed!” Their imaginations soar as they turn the dot into entire worlds.

Years later, those same students—now in fifth grade—see the same dot and respond cautiously: “A period at the end of a sentence?” “Part of a graph?” Their answers are practical, logical… and limited. By high school, the answers shrink further: “A dot.” The wild imagination that once transformed this dot into a universe has clearly faded.

This story mirrors a real phenomenon documented by creativity researchers. In 1968, George Land, who developed NASA’s divergent thinking test to identify innovative engineers, used a similar test on 1,600 children. He found that 98% of children aged 4–5 scored in the “genius” range for creativity. By age 10, that dropped sharply. By adulthood, only 2% remained in that range.

Though Land’s study wasn’t peer-reviewed, it sparked a deeper conversation about the loss of creativity in education. At the same time, Dr. E. Paul Torrance from the University of Minnesota was conducting a more rigorous longitudinal study, following 200 third graders over decades using his Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking (TTCT). His results were strikingly similar—children start school with high creative potential, which declines steadily through formal education.

Or as artist Ai Weiwei put it, “Creativity is part of human nature. It can only be untaught.”

Torrance also discovered something profound: creativity scores predicted lifetime achievement better than IQ or academic grades.

Reigniting Creativity in Education

Thankfully, there is hope—a growing movement to bring creativity, empathy, and curiosity back into education. I’ve seen this firsthand through my son’s experience at Design Tech High School (d.tech) in Redwood City, California—a public charter school founded in partnership with the Oracle Education Foundation and inspired by Stanford’s d.school.

d.tech’s mission is simple yet powerful:

“To develop people who believe that the world can be a better place—and that they can be part of making it happen.”

The school’s curriculum is built around design thinking and hands-on problem solving. Students learn empathy, collaboration, and creative confidence by tackling real-world challenges. At the heart of the school is a two-story “Design Realization Garage,” where students prototype, test, and iterate ideas.

When my son started at d.tech, I noticed many parents didn’t understand what design thinking was or why it mattered. So, I began teaching design thinking workshops for parents—helping them experience the same creative process their kids were learning. That shared understanding strengthened connections between parents, students, and the broader d.tech community.

The Innovation Diploma: Learning by Doing

One of d.tech’s signature programs is the Innovation Diploma. After completing design courses in their early years, juniors can take on a year-long social impact project tied to one of the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals. Guided by mentors and design coaches, students work in small teams to research, prototype, and implement solutions. Those who complete the program earn an Innovation Diploma—recognition for mastering real-world design and problem-solving skills that few high schoolers ever encounter.

Now, d.tech is beginning to offer this program to other schools, expanding its reach and impact. It’s a small but meaningful step toward scaling creativity-focused education nationwide.

The Spark Lives On

Every time I see a student light up with curiosity at d.tech, I think back to that carbon arc furnace. It was a reckless experiment, but also a powerful metaphor—a flickering spark of wonder that could have been extinguished or fueled into something greater.

The same is true in our classrooms, workplaces, and communities today. When we encourage safe exploration, creative risk-taking, and learning from failure, we ignite possibilities far beyond what any textbook can offer.

I often wonder: if my 12-year-old self had built that carbon arc furnace at d.tech instead of in my basement—how might that spark have further ignited my curiosity and creativity ?

Your Turn

If this story resonates with you, I’d love to hear your own “spark moment.” Was there a teacher, mentor, or experience that shaped your own creativity, learning, or leadership today? Share your story—because the more we celebrate curiosity, the more we keep that creative spark alive for the next generation.